Danica Clayton talks to a University of Iowa student and how growing up in Fontanelle, Iowa—a town of 600 people—shaped her past as well as future aspirations.

Featured image courtesy of the City of Fontanelle Facebook page.

Highway 92 slices Fontanelle, Iowa in half, leaving the playground and churches to the north and the funeral home and middle school to the south. When one drives down 92, it is rare to see kids playing on the playground. That’s not surprising for Fontanelle, a town of 600. One of those residents is Allyson Phillippi. She moved to Fontanelle with her family when she was four years old.

“My mom has always said, like, you are probably going to end up living in New York,” Phillippi said.

Her mom was only partly mistaken. Phillippi plans on moving away from Fontanelle after finishing her degrees Journalism and Graphic Design at the University of Iowa, which she is slated to receive in 2021. However, her plan is to move to Chicago instead of New York — she was not impressed with the smells and prices of New York.

With frequent visits to Chicago to see her boyfriend, she realized that the world is full of things she had never learned.

“It amazes me how many things are in the world, that I just didn’t know about, because no one in our town talks about it,” she said. “No one goes out of their way to experience new things.”

The draw to city life is in her nature. Phillippi has a bright, gregarious personality with an attraction to meeting new people and experiencing new things. For her, food is an important part of finding new experiences. All of those activities are nearly impossible to do in a town of 600 hundred people.

Yet through her years of competitive dance, she had opportunities to travel that gave her glimpses outside of rural Iowa.

“I feel like [dance] also played a very large part in why I wanted to get out, because I did have those other experiences,” she said.

Those experiences made the transition to Iowa City an easier, she said. Now, Iowa City has started to feel too small for her. She is ready for more, something that many—like her mom—have always seen in her.

City life is alluring because of its anonymity. As a person living in a small town, there is a lack of anonymity, and Phillippi being a teacher’s daughter heightens that feeling.

“I feel like being a teacher’s daughter put me even more in the spotlight,” Phillippi said, “I feel like every time I come home people are watching me.”

It is not surprising that everyone knows everyone in a graduating class of 52 people.

“I can literally sit here and name you everyone, their moms and dads, and their grandparents and their pets; literally everything about them,” she said of her high school peers.

Being out of high school doesn’t change matters. There is a culture of gossip in small towns, Phillippi said.

“They just talk about other people,” she said, “There is nothing else they have to talk about.”

Instead of talking about experiences and the world, she said she has noticed that people would rather just talk about others.

“There are so many little things I know about people, and I’m like, I shouldn’t know this,” she said shaking her head.

When the conversation wasn’t about gossip, Phillippi said she had to bite her tongue.

“Growing up in a small town, people’s political opinions, people’s everyday life opinions are very different from mine, and a lot of the time I would have to keep my mouth shut in certain conversations,” she said.

Keeping quiet has prevented disagreement and helped her learn ways to understand different viewpoints. This tactic is common in political discussions because Fontanelle is in a red part of the state, and Phillippi doesn’t always cosign to those beliefs.

But now she doesn’t want to be quiet. She uses her voice to stand up for others and to make sure her siblings, Avery and Annika, don’t get sucked into some of the small-mindedness and prejudice that emanates from small towns.

“If Avery says something [problematic] to me, first of all no, second of you never say that again, third of all if you hear any of your friends saying something like that, you are going to stop them from saying that,” Phillippi said with a fiery tone to her voice.

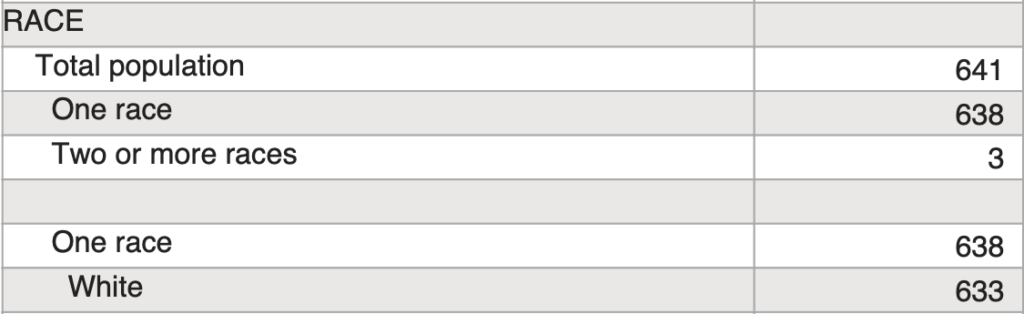

When looking at the demographics of Fontanelle, Greenfield, and Bridgewater — the other two towns that comprise Nodaway Valley Community School District — it is possible to count the number of families that aren’t white on one hand. That said, Phillippi ensures that her brother never says a discriminatory thing. This is especially important to Phillippi since her boyfriend is Mexican and Puerto Rican.

Her boyfriend has visited Fontanelle once before. The town was scarily quiet to him, Phillippi said, and he also wasn’t impressed with the Mexican food at the local restaurant.

She looks out for her siblings on many fronts.

“I don’t want him to feel like he has to stay there,” she said of her brother.

He feels the pull to stay in Fontanelle for work. She lets him know that he doesn’t have to do any of that.

“Go out and do what you want. If you want to be an NBA basketball player, make your fucking dreams come true. Go out and do it,” she said.

It is hard for dreams like that to come true in small towns though.

“Nobody’s going to see him because we’re from a small town,” Phillippi said. “Nobody’s going to pay attention to him and nobody’s going to see his skills because we’re from small town.”

“Being out of high school doesn’t change matters. There is a culture of gossip in small towns.”

She urged her mom to transfer him to a bigger school or a large AAU basketball team to make him more visible. Either way his story turns out, she wants her younger siblings to see the world.

“If you guys want to stay there that is all you, but do not marry that town,” she said.

She has seen plenty of people ‘marry’ Fontanelle; people who have never left the town and don’t plan on leaving.

“Go see something else that isn’t a corn stalk.”

While Phillippi strongly encourages people from small towns to go out and learn about other cultures, she does appreciate aspects of the small-town way of life.

“There is a very large support system,” she said as she remembered tragedies that impacted her area, “But when I think about it, would there be that support system if there were colored kids in our school system.”

Living in a small town nurtured her and gave her a support system she wouldn’t find elsewhere, as well as cultivating her desire to see more, understand cultures, and simply to see the world.

I grew up on a farm near Fontanelle. I could not wait to get out. I moved back to Fontanelle several times, the first time for three years on the farm with my husband. We were not accepted, but had friends in Greenfield. We moved to a town closer to Des Moines that was more accepting of people, and many commuted to jobs in Des Moines. About twelve years ago I moved back to Fontanelle because of elderly parents. I was not accepted and never invited anywhere except my one cousin who went to my church. I lived in my dad’s condo since he was in the nursing home. Some old women in the condo, who were older than me and less active, found out I was a democrat and screamed at me about Hillary Clinton and ostracized me from all activities. I went on and made my own life since my daughter and my grand sons lived just an hour away in Des Moines. I spent every other weekend there. Fontanelle is trump country and very prejudiced and snotty, anti woman as well as very racist. After my dad died I moved to Des Moines where my daughter and grandsons are and I am much happier in Des Moines. People are much nicer here and I don’t have to deal with the foul tempered, foul mouthed gossips anymore.